She made me a pinky promise

The emergency room at UCLA was the first time I’d seen my mother in nine years.

For so many reasons that span the length of my life, I had made the very difficult decision to cut contact with her, without any intention of reconnecting. It wasn’t the first time and so, I reasoned, it must be the last.

She wasn’t the kind of mother I’d insisted on becoming when Isaac came into this world. She wasn’t reliable or resilient. She wasn’t stable. Wasn’t safe. She wasn’t even really present after my parents divorced when I was seven. I think, perhaps, she must have been those things up until then, but it’s mostly after then that I remember.

After they split, we lived with our Baba, my sister and me. He wasn’t especially tender or affectionate but he was hardworking and funny and most of all, dependable. He did his best, that much I know to be true. He never spoke a word against her and protected us from their marital maelstrom. Even so, he took the brunt of her absence.

My mother was given court ordered visitation—every other weekend she was meant to pick us up, but rarely did. Car trouble was often the culprit, or so we were told.

And so, for most of the childhood that I’m able to recall, she was the sometimes-mom who was usually adventurous and fun and vibrant but every so often, violent. Often enough to be constantly braced against the possibility of an outburst. Often enough for those outbursts to be what I remember most.

My memories of my mother are measured in polarity: they were either the best or the worst, and increasingly became the latter.

It wasn’t without significant contemplation that I made the choice never to speak to her again, and it wasn’t for my own sake alone. I too was a mother, and I had promised myself to be everything she wasn’t: nurturing, steadfast, and most of all, safe. She’d had a few outbursts in the presence of my son and I vowed that he would not have to endure what I had, that his childhood wouldn’t be marred by violence at the hands of someone meant to grant love, unconditionally.

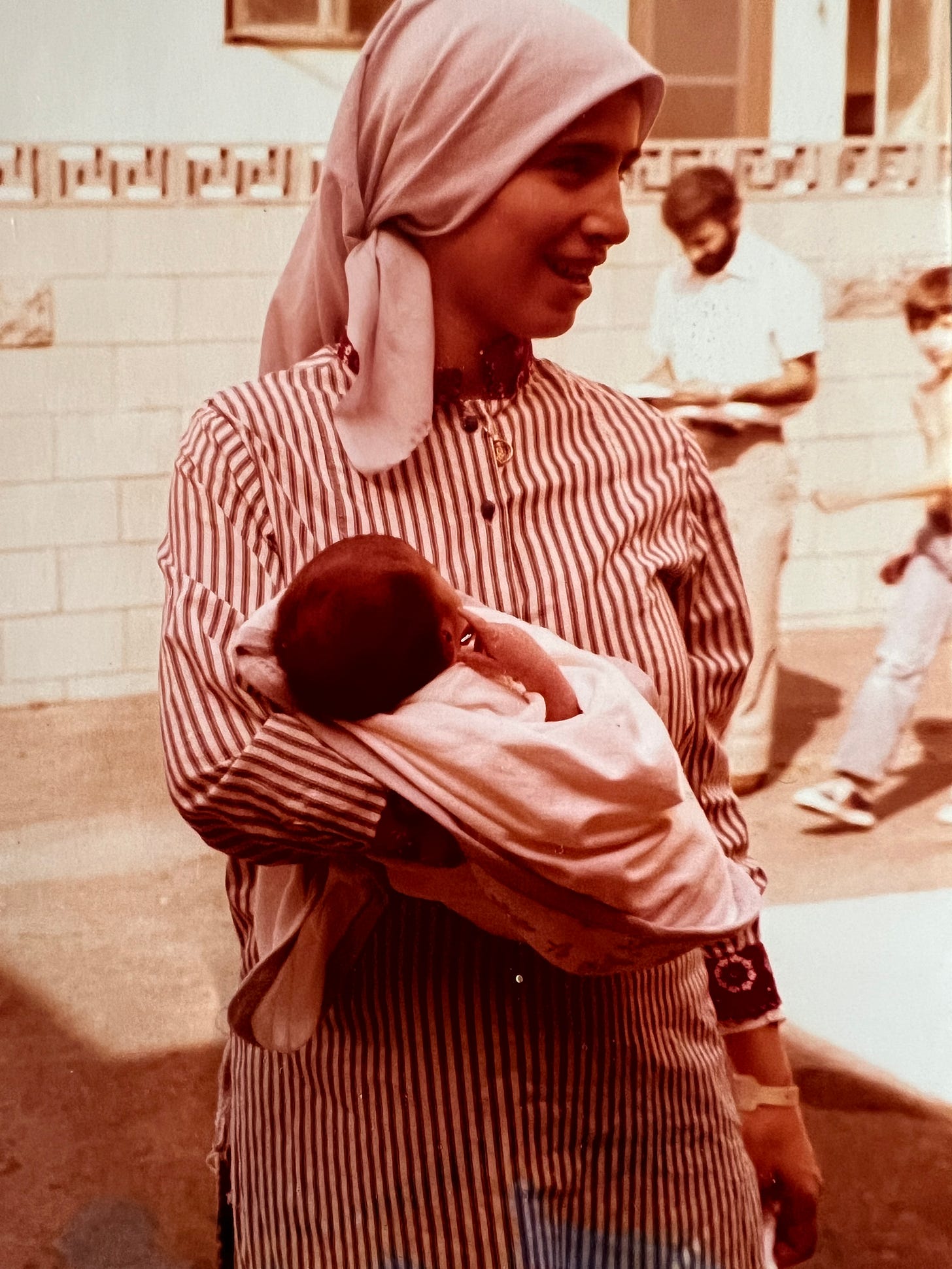

In the wake of our estrangement I sought and I found healing for myself, and forgiveness for my mother. I learned to hold space for my inner child, to give her what she didn’t receive when she needed it most. And I learned as well, to see the humanity in my mother’s violence—the unprocessed trauma from whence it came. In time, instead of anger or disappointment, I felt empathy for the young woman whose own childhood had been stolen from her, who was just a child herself when she was charged with bearing one of her own.

I think there must have been a reason she left me, a reason she couldn’t stay—and maybe it wasn’t that she didn’t want me. Maybe it wasn’t about me at all.

I decided that if the first and only selfless thing she’d done for me was carry me in her womb and bring me into this world, that it was enough. It was more than enough. Having done it myself, I understood the sanctity of that gift, and I was grateful.

But forgiveness doesn’t condone harmful behavior, nor does it require contact or reconnection. I had found my own closure, and I was content with to live out the rest of my life without her.

Last June, after experiencing extreme blood pressure fluctuations, heart palpitations, and sudden small fiber neuropathy, I called my older sister who in turn called my mother without my knowledge. Maman had worked her entire adult life in hospitals and, truth be told, was a good person to have around in a medical crisis. My sister knew this. She probably knew, as well, that every sick child needs their mother, no matter the distance, no matter the discord.

Ninety miles on the road and nine years of silence between us, she sat next to me in the ER waiting room and said, “I will always be here for you. I know you don’t really like me, but nevertheless, I’m your mom, and that means forever.”

I was sick and I was scared and I was, quite frankly, uncomfortable with her presence after so many years apart. All I could muster in response was, “It’s not that I don’t like you; I love you. It’s just that you’re so mean to me sometimes.”

She stayed with me in the ER and advocated for me in ways I would not have had the knowledge or bandwidth to do myself. After I was admitted to the hospital, she spent the next few days sleeping on a chair in my room, speaking to nurses and doctors on my behalf, waking every 20 minutes in the night when the machines connected to my body loudly announced that my heart rate had dipped into the low 30s. She demanded that every test be administered, every scan be done.

I hadn’t wanted her there, and I don’t know how I would have survived it without her.

A few hours before I was discharged, sensing that this respite from our estrangement would soon come to an end, she cautiously broached the idea that we might try and reestablish some semblance of a relationship. I’d had nine years to process—to grieve and grow and give up my anger. I had boundaries now, and I knew how to express them, how to protect them. More than anything, I had softened; it’s because of the softness that I found myself ready to receive her.

For her part, she was sober. She hadn’t had a drop of alcohol in years and was no longer abusing her pain medication. Her husband had passed from Covid and she was alone in a big house, desperate to make up for lost time, asking for a second chance all while acknowledging she probably didn’t deserve it.

It was easier than I’d imagined, our moment of reconciliation. Unremarkable, even. After nine years I suppose I’d expected it would require a lengthier deliberation—an airing of grievances, a discussion of terms. Instead I simply told her that I wouldn’t tolerate violence, verbal abuse, or mistreatment of any kind, and at the first sign of a violation I would be gone once more.

She agreed to my terms. She promised to respect my boundaries. I made her pinky promise, to both seal the deal and bring levity to an otherwise heavy exchange.

It’s been a year now, and she’s made good on her promise thus far. She’s remained my staunchest medical advocate, and a much needed support system during an uncertain time. We talk on the phone for hours; she gives me advice that I actually take. I visit her at least once a month; she cooks my favorite meals, a pot of ghormeh sabzi bubbling on the stove upon my arrival. We play backgammon. We watch My Big Fat Greek Wedding for the hundredth time. The serenity of her tucked away home has been a form of medicine, more potent than any my doctors have prescribed.

I’ve come to see more clearly the enormous blanket of pain that surrounds her, the way she wears it as if she hasn’t got a choice, the way it’s become so familiar to her it’s almost a comfort. I have grown in the sort of ways that allow me to meet her where she is, surprisingly willing to bend when it doesn’t cost me anything, soft against her edges where previously I’d recoiled from them. It’s extraordinary how differently you can receive the same things when you yourself have changed.

In the year since I first exhibited symptoms I’ve been to eight specialists and given at least 50 vials of blood. I’ve had six ultrasounds, two MRIs, an echocardiogram, a cat scan, a skin prick allergy test, and more panic attacks than I can count. I’ve cried in doctor’s offices out of exhaustion and frustration, and suffered the financial strain of living in a for-profit medical system. I’ve scaled every aspect of my life to accommodate the illness and a year later am without answers, without a diagnosis. And yet, I remain grateful.

Ram Dass once said, “I don’t ask for suffering but when it shows up, it certainly turns out to be grace.” Sometimes it takes a tragedy to unite a broken family, a trauma to mend something torn apart at the seams.

Had it not been for the mystery illness, I may not have ever reconnected with my mother. I’d made my peace with the lack of her, prepared to live the rest of my life as a motherless child. The magnitude of this second chance overwhelms me—not just her chance to be the mother she wished she could have been and the grandmother she never got to be, but my chance as well—to heal my inner child, to be her daughter in the second half of my life, in the last stretch of hers.